On August 16th, 2020, right before my first day of high school, my family and I drove 20 minutes South from our home in San Francisco to a small town called Pacifica in search of whales. It was an unusually cloudy day, with ominous clouds hanging over the horizon, poised to burst at any moment. We struggled to find a good parking spot at the beach we had planned on going to, Fort Funston, so we continued driving until we found a parking spot on a gravel road near an almost deserted beach. As we stood on a path overlooking the water, my younger brother pointed at some lightning on the horizon, and I instantly felt my heart leap with excitement. We never had thunderstorms in San Francisco, and I casually mentioned how happy I was that we were finally going to hear some real thunder and see some real lightning. My dad’s face darkened, though.

“I hope the lightning doesn’t cause any wildfires,” he said quietly, mainly to my mom, but loud enough for me to hear. I didn’t know this at the time, but the thunderstorm was actually from Tropical Storm Fausto near Mexico’s West Coast, which was basically a hurricane that didn’t actually reach Mexico. As we stood on that path, watching a pod of whales splash around in the water, I thought about what my dad had said. The lightning could indeed cause wildfires, especially in a place as dry as California. My glee was replaced with dread as I recalled the wildfires that had happened when I was in seventh grade. That year, school had been canceled due to the bad air quality caused by the smoky air, and I prayed that it wouldn’t be that bad this year.

Sure enough, on August 17th, 2020, exactly one day after the thunderstorm passed, the North Complex Fire began. I was quick to hear about this, but first, I smelled it and I saw it. Within the same week that the fire started, I went to the park with three of my friends to take a walk and have a socially-distanced picnic. As soon as I lowered my mask to take a bite of one of the cupcakes my friend had brought, I smelled smoke. Not cigarette smoke or smoke from barbecues, but wildfire smoke.

It only got worse from there. On September 9th, 2020, my mom woke me up in the morning. It was completely dark outside, so I thought that it must have been 5:00 in the morning. My heart automatically began racing, because, naturally, I thought that there must have been some kind of emergency.

“What’s going on?” I asked my mom, whose expression was unreadable.

“Nothing,” she said. “It’s 8:00, though, and you should probably get ready for school.”

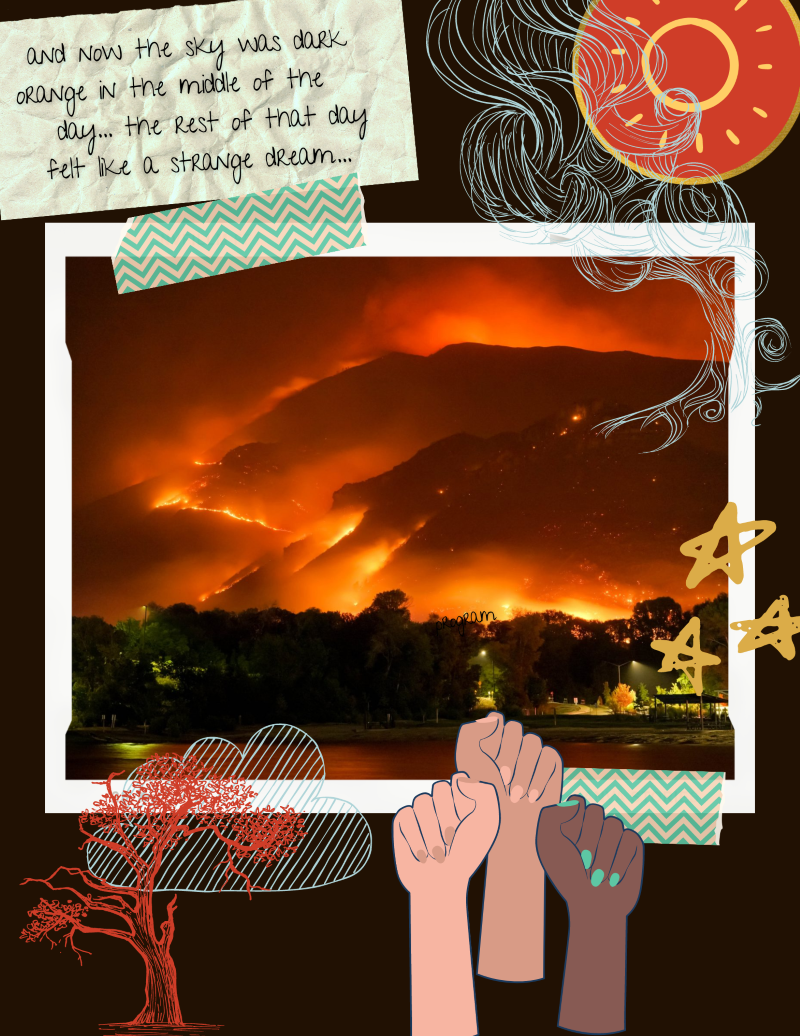

I was completely aghast when I opened my shades. The sky was a dark orange color, and there was no sun, not even a circular outline like there had been in the past. I was confused, astonished, disturbed, and terrified. I felt like I was in the midst of an apocalypse: a virus was ravaging the world, the only access I had to my peers and teachers was through a screen, and now the sky was dark orange in the middle of the day.

The rest of that day felt like a strange dream. I kept my lights on for the entire day, as did my classmates and teachers, whose houses I could see during Zoom calls. Nobody said anything about what was going on, which surprised me. My teachers acted like nothing out of the ordinary was happening, despite the fact that they all had their overhead lights on at noon. During my lunch break, my mom and I went outside onto our deck, and, surprisingly, my nostrils were not met with smoke; instead, the air smelled clean and wet. This, as I found out while combing the news for answers, was because of a pyrocumulonimbus cloud, which is a cumulonimbus cloud mixed with smoke. All of the smoke was up high in the atmosphere, so there was nothing to smell.

This memory stuck with me, and it occurred to me that events like these would become more and more common as climate change progressed. I felt helpless, until I finally decided to go to an information meeting for a climate activism group at my school. At that first meeting, I felt intimidated and a little scared. The group leaders talked boldly about different actions we might do if we decided to be a part of the group, and I was slightly nervous about some of these actions. Even so, I continued going to the meetings, even writing in my journal about how excited I was about joining the organization. I had to do something to help the world, to help stop climate change, and this seemed like a good organization to be a part of.

In late September or early October, we began planning a banner drop, and as time progressed, the details became clearer and clearer. We’d create a long yellow banner with thick black letters that read, “We have 12 11 10 years left. We need a Green New Deal now,” and we would hang it off of a bridge that was coincidentally very close to our school. This planning process was entirely new to me, and it was fun and also a little bit scary to be plunged into a completely new experience like this. The day before the banner drop, I was still debating whether or not I should go, consulting my parents multiple times about what I should do. Both of them nudged me forward, which I’m grateful for because if they hadn’t given me that necessary encouragement, I probably wouldn’t have gone.

The morning of the banner drop, I woke up with butterflies in my stomach and mixed emotions, including excitement, fear, confidence, and hesitance. Nevertheless, I got in the car after breakfast, and my dad drove me to the shopping area where everyone would meet with the banner, a box of zip-ties, and enough t-shirts for all of us. We made small talk as we waited for more people to arrive, and at one point, we all got into a messy circle and shared our names, pronouns, and which plant we felt like that day.

After doing some preparation in the parking lot of the parking area, we were all ready to walk to the bridge and drop the banner. The butterflies in my stomach were fluttering again, with nervousness, but also with excitement and pride. I was proud of myself for taking the necessary steps to raise awareness about climate change, and I told this to myself as we all got into the right positions for the banner drop, tying the banner to the bridge with zip-ties. The public relations team was taking pictures of us down below, and even though they were far from us and I was wearing a mask, I smiled widely, happily, proud that I had gotten myself to this point.

What happened next was simple: one of the group leaders counted down to zero, and we dropped the bright yellow banner. It unfurled beautifully and fluttered a bit in the breeze as we all admired our good work. One person driving on the road underneath the bridge flipped us off, which hurt, but most people either honked their praise or gave us thumbs-ups. The air was clean that day, and I thought about what the future might look like if our and others’ climate activism paid off. If we could get politicians’ attention through actions like these and get them to act as soon as possible, the results would be worth it, but we had to try. If we didn’t try, nothing would get done about climate change, and we wouldn’t have a livable future. But as I admired my and my peers’ work, I felt a jolt of optimism. I knew that if people continued doing work like this, there was a chance that we would get noticed, and that we would be able to make a change for the better.

I am so happy to see this experience shared for others to read AND remember. Continuation toward deeper connections to resolve climate change is necessary and your voice and the voices of many youth will be the key to human adaptation in global climate change . #youthvoices

Such a valuable and beautiful point, Angela 👏 We’re so grateful to have honest, fair, curious voices like Ava’s in our family of #grlmag contributors. We honestly can’t wait to see what she has to offer next 😍

Ava, That was a timely and important article. People think that just one person

can’t make a difference, and indeed, it is helpful to have many who care and

are willing to work together. I am proud of you for trying and I hope that you

continue to be active in this area.